Sensical Science

Making Bladder Pain Research Understandable

Living with bladder pain can be exhausting, confusing, and frustrating. Interstitial cystitis, sometimes called bladder pain syndrome (referred to as IC/BPS) is a condition where people feel long-term bladder pain, urgency, and frequent urination even when there’s no obvious infection or other explanation. Treatments can help some people, but many patients are left with only partial relief because we still don’t fully understand what’s driving the chronic pain.

This project looks at one possible piece of the puzzle: a complex part of the immune system called the inflammasome, which can act as an internal alarm system and keep inflammation and pain activated. We used a mouse model of bladder pain to ask a question: if we quiet down this alarm system, does the bladder hurt less and do the animals urinate less often?

On this site, I walk through what we did, what we found, and what it might (and might not yet) mean for people with IC/BPS. My goal is to explain the science in clear, accessible language while staying honest and true to the underlying biology and the data.

The patient experience

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) is a long-lasting condition where people feel pain, pressure, or discomfort in the bladder and pelvis, often along with a constant urge to pee and frequent trips to the bathroom. For many, the bladder can feel irritated or “raw” even when tests don’t show an infection, kidney stones, or other obvious causes.

IC/BPS can seriously disrupt daily life; bladder pain can affect sleep, work, relationships, and mental health.

People may need to plan their day around bathroom access, avoid travel or social events, and feel frustrated when their pain is hard to explain to others. To make things harder, IC/BPS is usually a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning patients are often diagnosed only after other causes of bladder pain have been ruled out, which can take years.

Right now, there is no single known cause and no one-size-fits-all treatment. Some people get partial relief from medications, bladder instillations, pelvic floor therapy, or diet changes, but many still live with ongoing symptoms. That uncertainty is part of why research like this matters.

By understanding what is happening in the body, we can start to design better, more targeted treatments.

What's going on in the bladder?

1

VEGF

More Blood Vessels and "Growth Signals"

People with IC/BPS may have higher levels of a molecule called VEGF in their bladder tissue and blood. This molecule encourages new blood vessels to grow and makes existing ones a bit leakier.

When this happens in the bladder, the lining can become irritated, swollen, and more sensitive than it should be, so normal filling or stretching starts to feel uncomfortable or painful.

Caspase-1

Internal Alarm System:

"Inflammasome"

Inside bladder cells, proteins like NLRP3, ASC, and procaspase-1 can interact with other molecules to form a complicated structure called the inflammasome. When this group is activated, procaspase-1 is turned into active caspase-1.

Caspase-1 is one of the body's signals that it is officially time to panic. It activates other messenger molecules, which tell more cells that there is a problem.

2

3

Cytokines

Inflammatory Messengers

"Cytokines"

Once caspase-1 is active, it helps produce inflammatory messengers called cytokines. There are many of these molecules, including IL-1β and IL-18, which have been found at higher levels in some IC/BPS patients.

There are many different cytokines in the body, each activated in different ways, but for this project these are the key players you need to know about.

How We Study This Pain in Mice

We can’t repeatedly irritate or biopsy human bladders just to test ideas, so we use a carefully controlled mouse model of bladder pain instead. The goal is not to perfectly copy IC/BPS, but to recreate some of the key features: bladder inflammation, pain, and changes in how often the bladder empties.

In this project, we used VEGF to irritate the bladder. While the mice are briefly under anesthesia, a small catheter is placed into the urethra and a VEGF solution is gently instilled into the bladder. This is called an intravesical instillation (literally “into the bladder”). The VEGF sits in the bladder for about 5 minutes, then is allowed to drain out. We repeat this three times to create a more long-lasting, IC/BPS-like state.

Over time, this VEGF treatment leads to:

-

A more inflamed and sensitive bladder lining

-

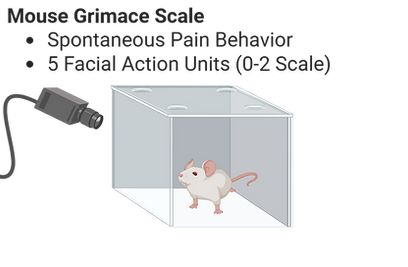

Increased pain-like behaviors, such as sensitivity to touch and facial expressions of pain

-

Changes in how often the mice urinate

The mice used were modified genetically so that we can visualize activated caspase-1 molecules. Simply put, the same gene that allows fireflies to glow was inserted into the genes of this mouse line. After we inject the mice with a harmless molecule called luciferin, tissues with higher caspase-1 activity give off more light, which we can measure with a sensitive camera. This allows us to see when and where the inflammatory signal is turned on in the body. The imaging system picks up on how much light there is, and we are most interested in the bladder and the regions of the brain that process pain, so we also create a "thinned-skull window" that allows us to see this activity in the live animal's brain. Just like a firefly.

Imaging the Inflammatory Response:

By combining this VEGF-based model with reporter mice, we can ask very specific questions:

-

Does extra VEGF in the bladder activate this inflammasome alarm system in the bladder and brain?

-

When we test drugs that prevent caspase activation, does the inflammation (bioluminescence) go down?

-

And do those changes line up with less pain behavior or urinary changes

Measuring Pain and Urinary Frequency

These three tests let us turn mouse behavior into data, so we can see how bladder inflammation changes pain and urination.

Experimental Groups

Because this was a pilot (early, exploratory) study, we started with small groups, comparing one thing at a time. We started with a VEGF bladder pain model and then added treatments and conditions as we learned what was feasible.

The main idea was to compare:

-

Mice with normal bladders (Saline instillations)

-

Mice with irritated bladders (VEGF instillations)

-

Mice with irritated bladders plus a drug that prevents caspase-1 from activating

Here’s how this looked in practice:

Step 1: VEGF vs. Saline

-

Male & Female: Saline (control) mice

These mice received gentle bladder instillations with a neutral solution (saline) instead of VEGF. The goal is to keep every other factor as close to the same across groups. -

Male & Female: VEGF-only mice

These mice got VEGF in the bladder to create irritation and an IC/BPS-like state. They tell us what extra VEGF in the bladder does on its own to pain, urination, and inflammasome activity.

Step 2: Blocking NLRP3 with an Injection

-

Female mice: VEGF + MCC950

In one set of experiments, female mice with VEGF-irritated bladders also received MCC950, a drug given by injection that blocks the NLRP3 pathway.-

MCC950 is not considered safe for humans, so this was more of a look into the mouse's reaction to the VEGF exposure. This drug is understood to block NLRP3 and nothing else, so a response brings insight into what is taking place on the molecular level.

-

Step 3: Testing a New Drug Directly on Bladder Tissue

-

In a small ex vivo (outside the body) experiment, we also tested VEGF with and without usnoflast (ZIYIL1) on isolated male bladder tissue and measured caspase-1-dependent “light” as a readout of inflammasome activity.

-

This gave us an early hint about whether usnoflast might directly calm this pathway in bladder tissue, as opposed to an injection.

-

Step 4: Blocking NLRP3 in the Bladder Itself

-

Female mice: VEGF + intravesical usnoflast

In another set of experiments, we focused on urinary symptoms. Female mice with VEGF-irritated bladders received usnoflast directly into the bladder.-

Comparing these to VEGF-only females let us see whether local NLRP3 blocking changed how often they peed in the void spot test.

-

-

Male mice: VEGF + intravesical usnoflast

In male mice, we again used VEGF to irritate the bladder and then added usnoflast into the bladder for some animals.-

For this group, we looked at spontaneous pain (grimace scores), stimulated pain (abdominal von Frey) and urinary frequency, to see whether the same pathway-targeting drug helped males in the same way it helped females.

-

The Results, Unpacked

Imaging:

Conclusion 1: VEGF exposure in the bladder of mice led to caspase-1 activity in the body and the brain.

Using our glowing-mouse imaging system, we looked at how active the brain and abdomen areas were after the bladder was irritated.

-

Mice with IC/BPS-like bladder irritation showed stronger brain signals than the saline mice mice, meaning some cell in the body sent alarm bells to the brain.

-

Later, we plan to image specific regions of the brain that involve pain-processing.

The Evidence:

Bladder

Brain

VEGF-treated mice show stronger “glowing” brain signals than saline controls.

Left) Sample IVIS images from one saline mouse and one VEGF mouse across four imaging sessions. Warmer colors (yellow/red) mean stronger bioluminescence, which reflects more activity in pain-related brain regions after bladder irritation.

Right) Average brain bioluminescence for saline vs. VEGF groups over time. VEGF mice show higher signal than saline controls after the 2nd and 3rd bladder treatments, indicating increased pain-related brain activity in this model. Statistical significance is marked at those timepoints.

Conclusion 2: Blocking the NLRP3 pathway with the drug MCC950 reduced caspase-1 activity in VEGF mice.

Mice received bladder instillations and then an MCC950 injection. When we examined their brain and bladder tissue 24 hours after the third treatment, the mice that got MCC950 had much lower caspase-1 activity than the untreated group, showing that the drug successfully reduced this inflammatory signal.

The Evidence:

To see if our glowing signal was really driven by a specific inflammation pathway, we did a test using freshly removed tissues from VEGF-treated mice and a drug called MCC950, which blocks the NLRP3 inflammasome (an activator of caspase-1). When we paired VEGF exposure with MCC950 injections, the bioluminescence signal went down compared to tissue given no drug. This suggests that the glowing signal in our model depends, at least in part, on NLRP3 activity, and that blocking this pathway can dial down inflammation-related activity.

Figure 2. Blocking the inflammasome with MCC950 reduces the “glowing” inflammation signal ex vivo.

Left) Sample IVIS images of brain tissue slices from VEGF-treated mice that were incubated ex vivo with either saline, VEGF, or VEGF with the NLRP3 blocker MCC950. Warmer colors (yellow/red) indicate stronger bioluminescence, reflecting higher inflammasome activity.

Right) Average bioluminescence signal for tissue treated with vehicle vs. MCC950. Slices exposed to MCC950 showed less “glowing” than saline-treated slices, indicating that blocking NLRP3 can reduce this inflammation-related activity. Statistical significance is marked at doses where MCC950 significantly reduced the signal compared to saline.

Conclusion # 3. Usnoflast shows early promise for calming this inflammation pathway.

The Evidence:

In a small side experiment in male mice (2 per group), we compared three groups: saline, VEGF, and VEGF + usnoflast. Usnoflast is a newer drug that targets the same NLRP3 pathway as MCC950, but is being developed with human safety in mind and may be better suited for future clinical use. Mice that received usnoflast tended to have lower caspase-1 “glow” than mice that got VEGF. Because the groups were so small, we can’t rule out the possibility that this difference was due to random chance. However, the steady downward trend in the usnoflast group suggests that blocking NLRP3 with drugs like usnoflast is feasible in this model and worth testing in a larger study.

Bladder

Brain

Figure 3. New NLRP3-blocking drug usnoflast shows early downward trends in brain and bladder glow.

A) IVIS images and average brain “glow” (bioluminescence) in male mice treated with saline, VEGF, or VEGF + usnoflast across bladder instillations. A visible downward trend appears in the usnoflast group after the first VEGF instillation, suggesting reduced pain-related brain activity.

B) Ex vivo bladder caspase-1 signal from the same groups. Bladder areas from living usnoflast-treated mice show a lower “glow” than VEGF + vehicle after the first instillation, consistent with early dampening of the NLRP3 inflammation pathway, although this test group was too small to detect statistical significance.

Pain Testing

When we blocked the NLRP3 pathway with the drug MCC950, VEGF-driven pain behaviors went down in female mice.

VEGF bladder instillations made the lower belly much more sensitive to touch. On the abdominal von Frey test, VEGF-treated mice pulled away from much lighter pokes than saline-treated mice. This increased sensitivity showed up 24 hours after the first instillation and lasted for at least a week after the third instillation. Mice that received MCC950 had higher withdrawal thresholds over this same period, meaning they needed a firmer poke before reacting. In other words, MCC950 reduced the VEGF-induced touch sensitivity.

We saw a similar pattern for ongoing (spontaneous) pain using the Mouse Grimace Scale. VEGF increased grimace scores in these female mice and those scores stayed high for at least a week after the final instillation. MCC950 brought grimace scores down at 3 days and 1 week after VEGF, suggesting less ongoing pain.

Conclusion #4: Blocking the NLRP3 pathway reduces touch sensitivity and ongoing pain in female mice.

Figure 7: MCC950 significantly reduce grimace pain score at 3 days and 1 week after the last instillation. Both plots: n=5/group; *p<0.05 for Saline vs. VEGF, #p<0.05 for VEGF vs. VEGF+MCC950, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD

Conclusion #5: Usnoflast: Effects on Ongoing Pain in Male Mice

In male mice, VEGF also increased signs of ongoing pain. Grimace scores were clearly higher in VEGF-treated mice, and this increase was reduced by usnoflast, suggesting that usnoflast can lessen spontaneous pain in this model.

Unlike in the female MCC950 experiment, the abdominal von Frey test in the male usnoflast cohort did not show clear differences in touch sensitivity between groups. Because there was no meaningful separation between treatments, those von Frey data are not shown.

Figure 8: Usnoflast transiently attenuated VEGF-induced spontaneous pain in male mice, with significantly reduced mouse grimace scores 24 h after the third instillation in the VEGF+Usnoflast group compared with VEGF alone (n = 5 per group; *p<0.05, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD); no other time points reached significance.

Urinary Frequency Testing

Conclusion #5: Usnoflast decreased IC/BPS-associated urinary frequency in female, but not male mice.

Voiding behavior assessed by void spot assay revealed a sex-dependent effect of usnoflast on IC/BPS-associated micturition frequency. In females, VEGF instillation increased the number of voids compared with saline controls, consistent with an IC/BPS-like urinary phenotype. Usnoflast treatment significantly reduced voiding frequency 24 h after the second and third instillations and again at 1 week after the third instillation, whereas effects at 3 days post-third instillation did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, in males, VEGF-induced changes in voiding frequency were not significantly altered by usnoflast at any time point, suggesting potential sex-related differences in IC/BPS-associated urinary pathology and treatment responsiveness.

Figure 9: Usnoflast instillations alleviated VEGF-induced voiding dysfunction in a small female cohort. (n=3-4/group; *p<0.05 for Saline vs. VEGF, #p<0.05 for VEGF vs. VEGF+ Usnoflast, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD)

Conclusions

-

MCC950 dampens inflammation signals. Blocking NLRP3 with MCC950 lowered caspase-1 activity in both brain and bladder tissue.

-

Usnoflast looks promising, but the sample was tiny. Early “glow” trends suggest usnoflast may reduce this same inflammation pathway, but we can’t be confident yet because the groups were too small.

-

MCC950 reduced pain behaviors in females. It decreased touch sensitivity and lowered signs of ongoing pain after VEGF.

-

Usnoflast may reduce ongoing pain in males. Male mice showed less grimace-related pain with usnoflast, even though touch sensitivity didn’t clearly change in that cohort.

-

Usnoflast helped urinary symptoms in females, not males. It reduced VEGF-linked frequent urination in females at multiple time points, but didn’t meaningfully change voiding in males. This hints at sex-specific disease biology and/or drug response.